Heliskiing and snowcat

skiing are perhaps the sport’s ultimate vacation, but each carries distinct

advantages and disadvantages for the experienced adventure seeker. The choices

at times can seem overwhelming. Let’s look at the world of British Columbia

beyond the chairlifts.

n

GEOGRAPHY 101

Let’s start with a geography lesson. Highway

5 is the demarcation between the Cariboo and Monashee mountain ranges. The

Cariboos are west of Hwy. 5 and are the northernmost range used for heliskiing. Crescent Spur and Robson Helimagic heliskiing operations are

in the northern Cariboos near Valemount. The Monashees are east of Hwy. 5

and follow the west side of the Columbia River to well south of Revelstoke.

Mike Wiegele’s permit area surrounds the town of Blue River along Highway

5. The Selkirks are across the Columbia from the Monashees, home to the Selkirk-Tangiers

heliski area across the Columbia River from CMH Revelstoke. East of that

is Rogers Pass in Glacier National Park, where only backcountry skiing is

permitted. The Purcells are farther east, parallel to Hwy. 95 from Golden

in the north nearly to the U.S. border in the south. Purcell Heliskiing is

near Golden and RK Heliskiing is in the Purcells just south of the Bugaboos.

Great Canadian heliskiing and Chatter Creek snowcat are located north of Golden.

As a generalization, the Cariboos and Purcells

offer mostly alpine and glacier skiing (the tree line is lower at 5,500 to

6,000 feet of elevation), while the Monashees are most famous for their tree

skiing. In the Selkirks the proportion of tree to alpine skiing varies by

latitude, ranging from mostly trees at Kootenay to mostly alpine at the Adamants.

Great Northern snowcat skiing is between Kootenay and Galena, and there are

four other snowcat operators in the Selkirks east and south of Kootenay.

Fernie and Island Lake Lodge snowcat are at the southeast corner of B.C.

in the Lizard Range, which has a localized microclimate similar to the southern

Selkirks. TLH to the west is much farther from the coast than

Whistler and similar to the Cariboos and Purcells in glaciated terrain. I’m

sure I’ve left out some operators, but by location and altitude one can make

an educated estimate of the terrain.

SNOWCAT OR HELI?

The obvious difference is cost (all quotes converted

to U.S. dollars). Most B.C. snowcat operators will cost about $1,000 for

a 3-day all-inclusive package. A 3-day heliski guarantee would run about

$1,800, but with cooperative weather expect to spend an additional $300-$400

for an extra 15,000 to 20,000 vertical feet. The normal CMH package is an

all-inclusive week including transport from the Delta Calgary Airport Hotel

with typical cost of $4,000 at operations based in town hotels and up to $5,000

at remote lodge operations. Single-day cat skiing without lodging is $200-$300,

or $400-500 for a heli with a low guarantee of 10,000 vertical feet or so.

The major uncertainty of heliskiing is weather.

In most seasons Canadian heli operators average less than one no-fly day per

week. One of the people I skied with at CMH Kootenay had been to six different

CMH operations, always for the whole week, and there is some compelling logic

for doing that if you can afford it. Losing a day to weather is not uncommon,

but over a week you’ll make it up with plenty to spare, unlike you may on

a 3-day trip. He said you can burn out, but then you just take a day off.

The standard week guarantee is 100,000 vertical feet, and at a typical CMH

operation you would get that pretty easily in 4-5 days of skiing. He had

never failed to make the guarantee on his other trips.

Heliskiing offers a greater assurance of powder

snow, with vast permit areas and access to higher altitudes. The mobility

can allow greater variety as well as quantity of skiing vs. a snowcat. In

particular, snowcats range no more than 1,000 vertical feet above timberline.

If you want predominantly glacier skiing, you should go for the heli. A possible

exception is Chatter Creek snowcat in the Purcells, where a helicopter is

used to transport skiers to its remote lodge.

Canadian snowcat permit areas tend to be much

larger than their U.S. counterparts and it would be quite rare for them to

get tracked out. At typically low snowcat altitudes there is a risk of spring

conditions by March if it hasn’t snowed recently. I therefore recommend sticking

to January and February for advance booking a snowcat trip. Untracked midwinter

powder really does stay light and dry for a couple of weeks in interior B.C.,

hard as that may be for us in southern or coastal climates to believe.

In March and later months a northern exposure

and altitude over 6,000 feet are needed to have similar confidence in snow

quality. Some of the heliskiing terrain goes up to 9,000 to 10,000 feet,

so well preserved powder into April is common on the glaciers. Conversely,

I believe that a snowcat is preferable to heliskiing in December and January.

The warm rides up the hill in the cat might be quite welcome during that time

of year, plus flat light in the alpine is most severe in the early season.

TREE SKIING VS. ALPINE/GLACIERS

The first consideration in deciding between terrain

above or below the tree line involves the effect that the timing issue just

discussed has on visibility. The alpine is preferable March and later when

visibility improves, and the trees have the advantage in December and January

when flat light days are common. February rates highly for either mountain

region.

The glaciers and high alpine have a unique aesthetic

appeal. On your first clear day up there you’ll burn up lots of film. It’s

easy to get in a rhythm of powder turns that are rarely experienced in a lift-serviced

environment. A fast paced group can really rack up the vertical, as it is

easier to keep track of everyone and not regroup as frequently as you must

in the trees. Nonetheless, tree skiing is considered more demanding, and

CMH advises inexperienced powder skiers not to choose an operation where tree

skiing predominates.

The advantages of the trees lie in snow quality

and weather. The snow is not affected as significantly by wind in the woods

and can be much deeper. While no-fly days are infrequent, there are many

other days when visibility is poor in the alpine and therefore skiing must

start at timberline. All three days that I have spent heliskiing in the Selkirks

plus one of my snowcat days at Island Lake Lodge near Fernie were in this

category. This weather factor is the reason lead guide Ken France at CMH

Kootenay chooses to work at that operation. All of the CMH lodges offer some

tree skiing in poor weather, but many of them are short vertical runs that

have been cut above the lodges. The higher tree line present in the Monashees

and most of the Selkirks yields a great variety of 2000+ vertical foot runs

of naturally gladed terrain.

Some of the heliski permit areas offer long fall

lines of both alpine and tree skiing. These would be Mike Wiegele (Cariboos

and Monashees), CMH Gothic (northern Selkirks and Monashees) and CMH Bobbie

Burns (Purcells and Selkirks). In addition the CMH and Selkirk-Tangiers operations

in Revelstoke have considerable alpine above their better-known tree skiing.

GETTING YOUR FEET WET

Skiing untracked powder from a snowcat or helicopter

is less tiring than the tracked or chopped powder one usually experiences

at a lift-serviced resort. However, falling (and particularly retrieving

and putting on equipment) is very exhausting, so it is understandable that

skiers with minimal powder experience could be apprehensive.

If cost is no object, CMH offers intro weeks at

several operations. These groups move at a more relaxed pace and have an

extra guide to assist with instruction. With fat skis the learning curve

is much faster than before. Otherwise, the best option for a first timer

would be the day heliskiing trips from Banff (RK or Purcell) or Whistler.

These offer three to six glacier runs for $400-$500.

While snowcat skiing offers more comfortable rest

time between runs, all of the Canadian cat operations I have tried emphasize

naturally gladed and often steep tree skiing. For first time snowcat skiing

I would recommend Grand Targhee in Wyoming and Blue Sky West near Steamboat

in Colorado. Both average 450+ inches of snowfall and have abundant terrain

with an intermediate pitch.

|

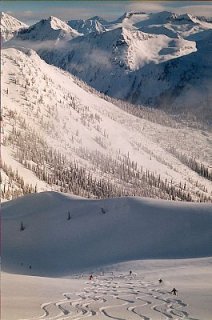

photo: Brian |

Experienced powder skiers should favor a multiple

day trip. On a single day trip the guides have to do the orientation/transceiver

drills and generally don’t get out onto the hill until 10:30 or 11:00 a.m.

They then have to evaluate the ability level of the group, which means they

are going to be conservative in their terrain choice for a couple of runs.

Single day groups may also have a disproportionate number of first timers

who may or may not be comfortable in powder. On days two and three at CMH

Kootenay, we were in the vans at 8:15 a.m. to head for the helipad. Also,

with multiple heliski groups the operator may reassign the skiers to another

group if there is too big an ability divergence. Thus, a "normal"

day with CMH, Wiegele or TLH consists of 9 to 11 runs.

CONCLUSION

The cost and remote locations in B.C. deter many

skiers from visiting these areas, yet I have observed several skiers who have

made inappropriate choices. Not only the stereotype punter beyond his depth,

but also the hotshot who blows $500 on three intermediate runs and wonders

what all the fuss is about. Nearly all of the B.C. operators have websites

(see links for heli-skiing and snowcat skiing operators), and careful browsing will usually reveal the type of skier

to which they are appealing. Do your homework and you may be rewarded with

the ski experience of your dreams.