Salt Lake City, UT – From the crimson cliffs of Bryce Canyon, to the startling expanse of the Great Salt Lake and the desert beyond, the Beehive State is an incredibly diverse collection of natural wonders. It therefore should come as no surprise that its bounty for skiers and snowboarders is no less diverse. Within 45 minutes of the immaculate downtown core of Salt Lake City, you’ll find no fewer than seven world-class resorts ready and able to cater to every whim and need, but each with its own distinct identity.

Where better, then, to consider a family ski getaway? You’ll avoid the familiar “Are we there yet?” syndrome, for anxious kids will only need to endure a 45-minute ride from airport baggage claim to check-in at any of the four resorts in Big and Little Cottonwood Canyons. After a flight halfway across the country, it’s refreshing to not have to face a two-hour drive in a rental car after landing, especially when you have your family in tow.

SNOWBIRD: MODERN CONVENIENCES

That proximity to the airport has other benefits as well. Thanks to an early morning departure from the East Coast and a two-hour time change, we were still able to board Snowbird’s tram shortly after noon for a full half day of skiing. Choosing Salt Lake City as a destination means that you need not lose a full day of vacation for travel.

We were on a mission to sample some of the best family ski vacation opportunities that Utah has to offer. My wife Patricia remains a struggling novice to lower intermediate who will, at the drop of a ski hat, abandon skiing for the day in favor of relaxing amongst the resort’s amenities. My 12 year-old son Michael, on the other hand, is a rapidly developing skier who’s bridging the gap from intermediate to advanced. He’s at the point now where he’s anxious for me to bring him along with me anywhere I want to go. He’s ready to take it seriously. As a family, we represented about as wide a range of abilities as anyone a group could have.

The main face of Snowbird is bisected by a spine ascended by its signature 125-passenger Aerial Tram, whisking skiers 2,875 vertical feet from base to summit in a scant six minutes. To climber’s left lies the Peruvian Cirque with one chair rising halfway. To the right sits the larger and more developed Gad Valley with its four chairlifts climbing from bottom to top and the Mid-Gad Restaurant at mid-mountain. In between, famous steeps like Great Scott and Wilbere Chute plunge from this ridge to these two valleys on either side. Behind the Tram on the mountain’s back side sits the relatively new Mineral Basin, where two high-speed quad chairs connect Snowbird and its neighbor, Alta Ski Area. A combined lift ticket for both ski areas is available.

Snowbird’s topography dictates that its strength will always remain in catering to experts, as its slopes and runs cascade down the steep walls of Little Cottonwood Canyon within sight of the Salt Lake metropolitan area. True novices are limited to several low-mountain lifts rising at most a few hundred feet above the base area: Baby Thunder, Wilbere and Chickadee. Big Emma has to be one of the steepest “green circle” runs anywhere. Patricia is thankfully a bit beyond the terrain serviced by those limited lift options, and Michael and I spent that first afternoon introducing her to the lay of the land by riding the Gadzoom high-speed detachable quad chair high into the Gad Valley, where low intermediate options were available to suit Patricia’s needs. In reality, this chair alone provides 1,630 vertical feet of skiing – as much as many ski resorts have in total. Michael zipped in and out of steep tree islands filled with shin-deep powder as Patricia motored by on the groomers.

These two resorts are each blessed by 500 annual inches of light, dry Utah fluff that the state’s ski resort association has trademarked “The Greatest Snow on Earth,” a description that’s more fact than fiction. The Wasatch Mountains are uniquely positioned to catch storms drifting in on either the southern or the northern jet streams. Pacific Northwest storms dive southeastward, and Southwestern storms angle to the northeast, both drawing a bead on Utah. After crossing a relatively flat expanse of desert, the orographic lift generated by the Wasatch Front forces the clouds to condense and deposit their white gold before drying out and heading east into Colorado.

Snowbird’s tight valley is also home to some of the state’s most luxurious slopeside lodging. The Cliff Lodge, our home for this visit, is a huge concrete and glass monolith – glass to provide views that are second to none, and thick concrete to withstand the brute force of the canyon’s infamous avalanches. The Cliff provides one-stop shopping for its guests – it’s virtually a snowbound mountain-based cruise ship. The top-floor Aerie Restaurant delivers a sushi bar and some of the finest dining in Utah, all with a first-rate view of the slopes. Guest rooms are cavernous, and the ground floor features rich wooden ski lockers, a rental shop, and a ski retail facility. The rooftop is home to the 28,000 square-foot Cliff Spa that’s a vacation destination unto itself. Three other similar but every-so-slightly lesser accommodations also populate Snowbird’s resort base.

Michael had big plans to take a few runs under the lights on the Chickadee chair, or ice skate on the Cliff’s outdoor rink, but his exhaustion from a morning of travel and an afternoon on the mountain got the better of him. After dinner, he soaked in the Cliff’s hot tub and splashed in the heated outdoor pool instead. As Patricia and I sat on the pool deck, clouds of steam rising from the water’s surface drew our gaze upward toward the moonlight-splashed flanks of a treeless Mount Superior. Countless stars twinkled in the cold, dry high mountain air. Tomorrow was another day, and we struggled to think of a more beautiful place in which to spend it.

ALTA: TRADITIONAL CHARM

Dinner conversation has never been a 12 year-old’s cup of tea, and Michael’s not much different than any other kid in that respect. My son’s nervous fidgeting in Alta Lodge’s nonetheless comfortable dining room began even before dessert had been served. Finally, he could take it no longer, and asked if he could go back downstairs to play again with Missy. Granted leave, he sped downstairs, and the conversation at the table resumed unabated.

Missy was the Alta Lodge staffer overseeing the game room during our stay, and after dinner concluded we descended the creaking stairs leading to the basement to find Michael engaged with her in a game of “Chutes and Ladders.” Watching for a few moments, it was hard to tell who was having a better time at it, Michael or Missy. My wife and I smiled to each other and went back upstairs.

Utah’s venerable Alta Ski Area breeds its own hard-corps reputation, thanks to its precipitous steeps, devoted following, and prodigious snowfall. It certainly isn’t widely regarded as a family destination. With so many families including a snowboarder these days, the fact that it’s one of the final holdouts that continues to ban snowboarding doesn’t help to foster a family-friendly image, either. We were soon to discover, however, that Alta provides a family vacation experience that takes no back seat.

Alta’s landscape is changing, and whether that’s for better or worse is in the eye of the beholder. With the installation of the new Collins lift this summer, skiers may now ascend from base to summit entirely on high-speed detachable lifts from either the Wildcat or Albion base areas. Curmudgeons will decry the demise of long, slow double chairs and cheap lift tickets, both of which have been replaced through Alta’s modernization, but also gone are the days when uphill capacity limited the vertical that could be skied in a day. Gone, too, are the uphill hoof to the loading area from the Wildcat parking lot, and the opportunity to lap the upper-mountain Germania lift, but families will be drawn to the speedy, comfortable ride that a detachable quad chair provides. Those same curmudgeons probably decried the demise of the Collins single chair when it was replaced in 1973 with a double, too.

One part of Alta’s landscape that can’t be changed is, well…the landscape. Alta is blessed by a topography that allows novices and low intermediates to enjoy the mountain from top to bottom. Rather than be relegated to lower mountain lifts, novices will delight in the ability to enjoy high Alpine panoramas from the Cecret, Albion and Sunnyside lifts, meeting more advanced family members at the mid-mountain Alf’s Restaurant for lunch. Intermediates can cruise down Little Dipper, Razorback and Devil’s Elbow, while experts can drop through Glory Hole or hike out to the steeps of Devil’s Castle, and all can ride together aboard the Sugarloaf lift back to the top.

Alta’s layout is reminiscent of the back of your own right hand. Alta’s two base areas reside on either side of your wrist – Albion on the left, and Wildcat on the right. Between them, across the back of your wrist, sits the tiny hamlet of Alta deep in the narrow head of the box-end Little Cottonwood Canyon. The thumb represents the Albion and Sunnyside lifts, rising above gentle, groomed wide green-circle boulevards. The index finger stands for the Supreme lift, rising steeply above Albion to the Catherine’s Pass backcountry access gates that eventually lead travelers across to Brighton in the adjacent Big Cottonwood Canyon. The middle finger would be the Sugarloaf chair, reaching Sugarloaf Pass, Alta’s highest lift-served point and the place where Alta’s terrain meets neighboring Snowbird’s. The ring finger is the new Collins detachable quad that heads straight up from the Wildcat base before turning 30 degrees to the left at its halfway point and heading to the top of Germania, just below Sugarloaf pass. Finally, the pinky is Wildcat itself, a low elevation area of steep tree skiing often overlooked by powderhounds in their quest for the fresh.

The valley floor at Alta is dotted with a number of cozy lodges where the atmosphere speaks of a ski era gone by. Every guest dines at their own lodge for breakfast and dinner, seated together with strangers to swap stories of the day’s exploits. All offer ski-in, ski-out accommodations, so some family members may sleep in while others rise with the dawn for first tracks. The end of each day is but a short ski away from the lift.

The Alta Lodge sticks to its traditions, and that’s a policy that brings guests back year after year. You’ll find no televisions in the rooms, a fact which at first shattered Michael, but it forced him to discover that there’s more to be gained by congregating in the common areas and sharing the joys of Alta with his fellow guests. His time spent downstairs with Missy, a few games of ping-pong, and Alta mayor (and Alta Lodge owner) Bill Levitt’s engaging stories quickly made him forget about Nickelodeon and the Disney Channel.

Skiing with Michael has always been fun, but thanks to his rapidly developing abilities, it’s been a real joy as of late. I was eager to show him the terrain that gives Alta its reputation as an expert’s heaven, and we led my wife to the Sunnyside lift before moving on ourselves to more challenging runs.

It didn’t take Michael long to catch on, for it was on our first ride up the Sugarloaf chair that he suggested hiking up the ridgeline to Devil’s Castle in search of some untracked lines. I led him first up the short bootpack, then onto the traverse below the cliffs above to reach hundreds of verts of steep stairstep terrain to the base of Supreme. Our second run was even more successful in finding fresh snow, traversing wide into the Catherine’s Pass area beyond where most others had dropped in. His grin was as wide as the opening on his helmet would allow.

After rejoining his mother for a few runs, we were off again in search of the goods. Alta’s convoluted topography remains a mystery to most first-time visitors, and I racked my brain to recall the routes to access some of my favorite steeps from years past to share with my son. Jitterbug, High Nowhere, High Greeley, and the Wildcat trees were all engraved that day into Michael’s grey matter, and his heart. Alta is now a place that he longs to return to.

Like father, like son.

PARK CITY MOUNTAIN RESORT: SYLVAN SURPRISES

Hop in your car and head 45 minutes east of Salt Lake City on Interstate 80, cross Parley’s Summit to the other side of the Wasatch, and things are suddenly very different. Although only a single mountain ridge separates them, the Park City area is a world apart from the Cottonwood Canyons. Sharp, jagged mountains are replaced by smooth, rolling summits. A tight canyon floor is replaced by a broad agricultural valley. Thinly treed slopes are replaced by healthy stands of aspen. The rarified air of the lofty ski area bases in the Cottonwoods is replaced by the more oxygenated air in the vibrant resort town of Park City, nearly 2,000 feet lower, but lop 150 inches off the annual Cottonwood snowfall averages, too. And the ski areas of Alta, Snowbird, Brighton and Solitude are replaced by Park City Mountain Resort, Deer Valley, and The Canyons.

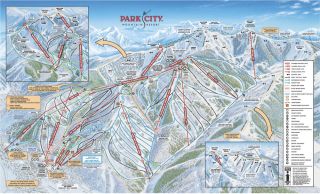

Park City Mountain Resort is a sprawling ski area with lifts spanning 3,300 acres of multiple summits and drainages that reach right down to the center of town. At its northern end, a thoroughly developed resort center offers shops, restaurants, and all manner of condominium lodging. At its southern end, the Town Lift rises from a square right on Main Street in the center of a bustling little downtown populated by genuine western architecture – 64 of Park City’s buildings are listed in the National Historic Register, with most of those in the downtown core. A skier bridge crossing Park Avenue returns skiers and riders from the mountain to its lift queue in Old Town. Park City Mountain Resort, and the town of Park City, are fully integrated with one another.

The choice of lodging options in a community with 21,500 guest pillows is immense. We eschewed the mountain’s Resort Center and opted instead to stay in the downtown core at the Park Station Condominium Hotel for the duration of our visit,in order to avail ourselves of all that the bustling 7,000-person community had to offer. More than 100 restaurants, coffee houses, micro-breweries and nightspots were within an easy walking distance, as were such conveniences as ski shops and corner markets, although a free bus system connects the town and all three ski resorts from 7 a.m. through 1 a.m. daily. Park Station sits a mere half block from the Town Lift and the skier bridge.

On paper, Park City is clearly oriented toward a family vacation. The ski area is known for its wide, gentle cruisers that sweep their way down the mountainside. Virtually all are accessible via a high-speed quad or six-pack chair (the latest of which, a replacement for the First Time chair for beginners, is new this season). Sprawling on-mountain restaurants and preserved mining remains both pepper the hillsides. The resort’s four terrain parks and two halfpipes are immense, and one of each is illuminated for night use. Short, steep shots drop from Jupiter Peak and Pinecone Ridge, on either side of Jupiter Bowl, but this isn’t the terrain that Park City is known for. Park City has a reputation as a cruiser hill.

Or so we thought. Park City has another side that isn’t readily visible on the trail map. In fact, this side is defined by what isn’t on the trail map: acres and acres of perfectly spaced aspen trees that few visitors seem to avail themselves of.

And we have the Battersby family to thank for it. Michael and I started our day with Debbie Battersby, a Park City mountain host spending her first full winter with her family in Utah after relocating from Illinois. The family’s assimilation is already complete, as daughter Ashley is a member of the Park City All-Stars as an up-and-coming freeskiing diva. Ascending the Town Lift, Debbie’s cell phone rang – it was her husband, Bill, an instructor at Deer Valley, and Debbie inadvertently had Bill’s lift pass in her pocket. A quick detour to the base of the Payday lift to deliver the pass was all that was planned, but in the end, the afternoon shadows were growing long before we all went our separate ways.

Riding the Payday lift together, it became apparent that Bill has a nose to sniff out beautifully spaced trees with a perfect exposure. Avoiding a nagging crust that clung to south-facing slopes, we stuck to the dry north sides of the ridges. After working our way across the mountain, Bill quickly dispelled Park City’s cruiser myth as we dropped into Isle of the Giants, an incredibly steep glade in the dark conifer forest of Jupiter Bowl. Adrenaline rushed as eight feet of vertical dropped away with each turn, the snow sloughing below us as it – and we – slithered between the trees. This wasn’t the Park City we’d expected!

We made countless descents through the north-facing aspen forests adjacent to the King Con, Silverlode, Motherlode and Thaynes lifts, laying first tracks in boot-top powder on nearly every run. Virtually every island of trees between trails was a pure delight. And we had it all to ourselves.

Park City owes its town legacy – and its ski runs – to its rich silver mining history. Incorporated as a city in 1884, more than $400 million in silver ore was extracted from the hills surrounding town through silver mining’s heyday. With the industry’s downturn, United Park City Mines, the last operating mining company in Park City, turned to skiing in 1963 with the help of a federal loan designed to boost the fortunes of economically depressed areas. Four decades ago, $1.2 million bought a base-to-summit gondola, lodges at each end, a J-bar, a chairlift, and a nine-hole golf course to create Treasure Mountain Ski Area, now Park City Mountain Resort.

In the early years, United Park City Mines made full use of its facilities to develop Treasure Mountain. The “Skier’s Subway” was a train run on old mining track through the Spiro Tunnel, but a tiny fraction of the more than 1,200 miles of tunnels bored through the hillsides surrounding Park City. At the other end of the Spiro Tunnel lay the Thaynes Hoist, which lifted riders 1,750 feet to the surface near the present-day Thaynes chairlift. In fact, most lifts and trails at Park City Mountain Resort are named after mines and claims on the surrounding hills. Exhibits chronicling Park City’s rich history may be enjoyed at the Park City Museum in the heart of Old Town at 528 Main St.

Eventually, 4 p.m. arrives, your quads give out, or both. If you’ve got the energy, skiing at Park City continues from the Payday lift under the lights until 7:30 p.m. We didn’t. We instead gave our quads a break and headed into town, sipping margaritas and refueling with the authentic Mexican and South American cuisine of Zona Rosa (501 Main St.). After strolling back to our condo, we lit a fire in the fireplace as Michael changed into pajamas and plopped down on the couch in his customary position in front of the television set. Light snow fell outside as we prepared for a morning sampling another of Park City’s three ski areas: Deer Valley.

DEER VALLEY: CREATURE COMFORTS

Deer Valley is a relative newcomer to the ski scene. Snow Park, Park City’s first ski area, opened with a T-bar in 1946, and Deer Valley was developed atop the ruins of that long-defunct ski area in 1981.

The choice to refer to the “ski scene,” and not the “ski and snowboard scene,” is an intentional one, for Deer Valley joins Alta amongst the four major U.S. resorts to continue its ban on snowboarding. Any effect this may have on the family visitor, however, is transparent, for the downstairs locker room in the Snow Park Lodge was filled with parents fitting boots, hats and mittens on their children for a day on

the slopes.

Like all facilities at Deer Valley, the Snow Park Lodge is both sprawling and opulent in the “parkitecture” style, as the resort has well earned its tongue-in-cheek moniker, “Dear Valet.” Mountain hosts help to unload guest vehicles in a large drop-off area that sits atop limited covered parking, where shuttles drop visitors parked in more distant lots off at the head of an indoor hallway leading to the lodge. Two novice double chairs here are complemented by a pair of quads that lift visitors up and over Bald Eagle Mountain, past opulent homes of television stars and movie moguls, to the Silver Lake Lodge. This is the jumping-off point to the majority of Deer Valley’s terrain, most of which is groomed to immaculate corduroy perfection to satisfy the resort’s discriminating guests.

Although draped across 1,750 acres with an overall vertical drop of 3,000 feet, most of Deer Valley’s terrain is digested in much smaller bites. Runs on Bald Mountain and Flagstaff Mountain, two of Deer Valley’s more popular summits, max out at 1,200 or so verts, and the full 3,000 feet are only skiable when descending all the way across high-priced homesites to the base of the Jordanelle Gondola beside U.S Route 40 via a long, long combination of lifts and trails.

With the exception of the Mayflower, Empire Express and Sultan chairs, runs for all abilities are accessible from every lift, enabling even a family of varying ability levels to ski together and stay together throughout the day. We took full advantage of this layout, and while the three of us often shared a run from top to bottom throughout the day, at other times Michael and I would momentarily dive into the trees or carve wide arcs on a steeper route while Patricia would plug on around the corner via a green circle cruiser.

As their terrain literally abuts one another’s, Deer Valley and Park City Mountain Resort share many characteristics. Both have clientele that by and large leave the powder in the trees for a select few, a well-guarded secret amongst powder hounds in these parts. Both are scattered about with fascinating

mining remains. Both sit in close proximity to Park City itself. Both have relegated their most challenging terrain to a single lift: Jupiter Bowl at Park City Mountain Resort, and Empire Canyon at Deer Valley.

There are differences, though, beyond their respective treatments of snowboarding. Foremost amongst these differences is the level of luxury that Deer Valley provides. Deer Valley has spared no expense to enhance the guest experience. Owners Edgar and Polly Stern applied their background in the luxury hotel and real estate business to their fledgling ski area in 1981, a concept theretofore unheard of in the industry. Lift ticket sales are limited to 6,500 daily to eliminate the potential for overcrowded chair queues on the 21 lifts that boast one of the highest hourly uphill capacities in the country. On-mountain meals, literally second to none anywhere within or without the ski industry, are served on china instead of on paper plates. As resort spokesperson Christa Graff aptly describes it, “Deer Valley Resort attends to the details, so all that guests need do is enjoy.”

That china is displayed in no fewer than 10 on-mountain eateries, serving up everything from gourmet burgers to wild game and seafood dishes and elaborate desserts, providing a rare European-like ski experience in the States. Meals at Deer Valley are something to linger over, not rush through, including fireside dinners at Empire Canyon Lodge featuring raclette, stew and fondue served from the Lodge’s three grand fireplaces after arriving at the Lodge via snowshoe, cross-country ski, horse-drawn sleigh, or automobile.

We arrived for our noon reservation at the Royal Street Café adjacent to the Silver Lake Lodge, starting with a sampling of scrumptious appetizers, including the lobster margarita featuring hunks of lobster tail and claw meat topped with papaya salsa and guacamole. My roasted game hen pot pie, with asparagus and shiitake mushrooms as well as braised baby onions encased in a manchego mashed potato crust, was just the fortification I needed to return to a full afternoon on the slopes.

Consistent with their guest service philosophy, Deer Valley has spent no less than $8 million this past summer to enhance the visitor experience for 2004-05. Two new chairlifts, a fixed-grip triple and another high-speed detachable quad, and two new lower intermediate runs have been added to Flagstaff Mountain. A new rail park has also been added to the Ore Cart run in Empire Canyon, adjacent to the skiercross course. Restrooms at both Snow Park and Silver Lake Lodges have been fully renovated. Deer Valley’s reputation for unblemished corduroy has been enhanced by the replacement of a whopping six groomers with brand-new machines.

LEAVING PARADISE IN THE REAR-VIEW MIRROR

Checking out of the Park Station condos, Salt Lake International Airport is only 29 miles away, enabling us to choose between a final morning on the slopes or a drive into the desert before catching a mid-afternoon flight back to the East Coast. We opted for the latter, however both options still allow vacationers to show up for work or school bright and early the following morning. Salt Lake City International Airport is serviced by 16 carriers, including AeroMexico, America West, American, Continental, Frontier, JetBlue, Northwest, SkyWest, Southwest and United, and serves as a hub for Delta. 800 flights arrive at and depart the airport daily.

Perhaps the best part about taking a family ski vacation via Salt Lake City is that this entire itinerary, visiting four dramatically diverse mountains, is easily accomplished on the same trip. In fact, it could easily be expanded to seven, eight or nine resorts without any difficulty as all are no more than approximately an hour from each other. Your only limitation is your willingness to pick up and relocate for the day, although combinations of Snowbird and Alta, Brighton and Solitude, or the three Park City ski areas of Deer Valley, The Canyons, and Park City Mountain Resort may each be accessed from a single lodging location without the need for extensive ground transportation.

To quote the favorite phrase of many a Utahan, “It’s all good.”

SKI UTAH INTERCONNECT TOUR

The close proximity of the ski resorts east of Salt Lake City to one another allows Ski Utah to display a slice of the Wasatch backcountry to visitors via its Interconnect Tour. Experienced guides lead guests in a single day through the sidecountry sandwiched between as many as six lift-served resorts, an experience not possible outside of Europe.

Tours depart either Snowbird or Deer Valley on alternating days from mid-December through late April, conditions and weather permitting, and travel through Alta, Park City Mountain Resort, Brighton and Solitude. Lunch is provided at one of the many on-mountain restaurants en route.

The backcountry snow and scenery between the resorts are nothing less than spectacular. The price of $150 per guest includes guide service, avalanche transceiver use, lift access, transportation back to the point of origin, lunch, and a special-edition finisher’s pin. Strong powder skiing skills are a must. The entire route is designed to be accomplished on Alpine ski gear, although some hiking and traversing is required.

For more information, visit www.skiutah.com.