Stratton Mountain, VT – Everyone has their reasons for skiing or snowboarding.

Some want nothing more than to carve perfect c-turns down a groomed trail, while others dream of floating through deep, untracked powder. There are those who think of nothing other than zipper lining moguls or straight lining steep pitches. Many spend entire days in the park riding rails, table tops, and half pipes. Parents look forward to reconnecting with their kids without having to compete with the TV or internet. I know a few people who make a couple quick runs and then go to the resort parking lot and party for the rest of the day. Fair enough.

But no matter which of the above lures people to a lift-served mountain, the common denominator among all of them is the concept of “escape.” It’s all about getting away from whatever ails you: crowded cities, faceless suburbs, mind-numbing 9-to-5 jobs, stressful commutes, inconsiderate husbands, irate wives, the shackles of gravity, and so on. Escaping into a snow-covered landscape surrounded by crisp, unpolluted mountain air makes it all go away, if only for a few hours. That’s why we do it.n

It’s fun, it’s healing, it’s liberating, but here’s the fine print – skiing and snowboarding costs serious money. Factor in lift tickets, equipment, clothes, base lodge food, lessons, and the costs of getting to the mountain, and you’ve got a sport that, to put it diplomatically, ain’t for the common man (or woman). Snowboarders in particular – many of whom aren’t out of college, let alone high school – are often hit the hardest unless their family has a decent level of financial resources or there’s an inexpensive hill nearby. The ultimate irony is that despite snowboard culture having completely co-opted urban language, attitudes, graphics, clothing styles, and music, with the exception of a few hills near big cities on the coasts, seeing inner-city or minority kids at a ski or snowboarding area is still a relatively uncommon event.

Snowboarding pioneer Jake Burton signs a fan’s hoodie. |

Realizing in 1995 that the sport they had popularized was often inaccessible to those not born into specific socioeconomic groups, Jake Burton Carpenter and his wife Donna leveraged their Burton Snowboards empire to found Chill Foundation. Designed to bring snowboarding to teens who otherwise wouldn’t get the opportunity, Chill has, from its headquarters in Burlington, Vermont, now touched the lives of more than 14,000 underserved kids spread across 14 North American cities. After launching programs in Innsbruck, Austria and Sydney, Australia last year, Chill just closed the books on a season that served more than 2,200 youths. If that’s not enough, plans are underway to expand Chill’s existing snowboard-based model to include surfing and skateboarding, as well as increase its involvement in community projects like bicycle-building, green-up days, and clothing drives.

So that’s more or less what I knew about Chill when I walked into their vibrant tent at the U.S. Open Snowboarding Championships at Stratton, Vermont last month. It sounded like an organization with a laudable Robin Hood-style mission – redistributing an experience that is usually restricted to privileged economic classes. However, after speaking with everyone from Jake Burton on down, it became clear that Chill goes several steps further than that. Instead of being a one-way charity, it teaches kids the skills needed to be productive and successful in whatever they do. What’s more, it gives them the means to make a difference in other people’s lives, too.

While the Chill saga began in the mid 90s, the turning point for the organization came about five years later, when staff members and social-service agency partners began discussing how the growing learn-to-ride program might be able to leave a deeper and more lasting impact on underserved kids. From its inception, Chill’s coordinators, managers, and directors were painfully aware that the youths who had been taking part had far bigger issues to deal with every winter than “which snowboard should I buy?” or “where should I get a season pass next year?” Most had been living amidst dysfunctional home and community environments filled with poverty, crime, homelessness, domestic violence, unemployment, even war. With parents often incapable of making proper decisions due to drugs, alcohol, incarceration, lack of money, or a combination thereof, these kids were often forced to take on the role of guardians to themselves, younger siblings, sometimes even to the parents themselves.

Chill coordinators stretch out at the summit of Vermont’s Stratton Mountain ski resort. |

Chicago coordinator Jude Gonzalez had an unsettling story about a happy-go-lucky 16-year-old he had brought to the U.S. Snowboard Championships a few years ago. “In the airport, he told me how great it had been to fly to Vermont and ride on the same mountain as some of the world’s best snowboarders, and that he’d tell his son about it one day. It took all of my acting skills not to let my mouth drop to the floor – I had absolutely no idea that this kid was the father of a two-year-old! We knew him as a typical teenager who loved to joke around with everyone, but he had a situation at home that none of us were aware of.”

Giving these young people a change of scenery is the foundation that supports the entire Chill program. Taking them into a new physical context separates them, at least temporarily, from issues that prevent them from being themselves, that’s to say: kids. For the first time in many of their lives, they experience a form of Zen, where, without having to think about it, the snowboard seems to be doing the work for them. More importantly, it allows them to realize that there are options to what they experience every day.

It doesn’t matter if they’re going to Summit-at-Snoqualmie near Seattle or a 97-vertical-foot molehill outside of Chicago, the snowboard areas represent a break from their often sobering home lives. National Coordinator Ryan Townsley compared being on snow to working with a clean slate: “There are no pre-existing expectations or pressure from school cliques, teachers, or their families. They can get outside themselves and understand how negative thought processes might be preventing them from reaching their full potential, and have a massive amount of fun in the process.”

The most critical step in developing Chill’s model was provided by social service agency partners, who worked with the organization to develop a six-theme curriculum designed to provide a psychological underpinning for the snowboard techniques they were learning. These codes (patience, persistence, responsibility, courage, respect, and pride) are, in reality, camouflaged life lessons. On the bus ride to the resort, the local coordinator uses engaging verbal or written exercises to introduce the theme of the day and connect it to any number of snowboard-related issues – for instance, the importance of closing the safety bar on the chairlift, giving the person downhill the right of way, not getting easily discouraged when they don’t immediately learn a new skill, or overcoming fear. Everyone is encouraged to talk about what the concept means to them not only in a mountain context, but also to reflect on the ways they may or may not be using it in their daily lives.

Underscoring the importance of how and where this curriculum is delivered, Chill Manager Jason Hirsch explained, “Instead of being presented at school, home, or in a social worker’s office, these themes are introduced in a winter-sports context by incredibly talented coordinators. They not only serve as positive role models, but also speak to the kids in ways that help them understand and absorb these ideas.”

After arriving at the ski area and gearing up in the lodge, instructors (provided by the host resort) give 1.5 hours of on-snow lessons. During the subsequent 1.5 hours of free riding, the kids work on what they had just learned – and that’s where the themes discussed on the bus start taking root. Jude Gonzalez explained, “If they fall down, get cold, or can’t figure out how to do something, they’re encouraged to be persistent and to keep trying until they succeed, as opposed to giving up and hanging out in the lodge.”

So instead of allowing their histories of physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual abuse lead them back to self-destructive behaviors, the kids learn to take back control of their destinies and understand that if they really apply themselves, anything is possible. Mastering a new snowboard technique or learning the importance of on-mountain etiquette makes them realize that they can navigate through new situations and different cultures – skills that will be critical if they move away from their families to go to college or to accept a job in a new location.

Participants also learn that Chill isn’t an entitlement program. Participating agencies and schools lay down a clear set of rules about the importance of responsibility, commitment, and respect, including formally recognizing the outlay of resources and efforts donated by the resorts, instructors, and volunteers. Jude Gonzalez explained, “The kids take this task very seriously and run with it. They write these incredibly heartfelt thank-you notes! People are sometimes surprised when they meet our allegedly tough, streetwise youths and see how polite, articulate, and genuine they are.”

After the six-week snowboard program has concluded, Chill conducts extensive follow-up through social service agencies and schools to monitor everyone’s ongoing progress. In addition, many former participants come back the following season to become “peer leaders,” ready to provide support to incoming youths. Peer leaders are especially valuable because they’ve gone through the program and can understand what new participants are experiencing and give them useful advice.

Among the memorable Chill kids I met at the 2009 Snowboard Championships was Mohammad (appropriately known among the group as “Mojo”), a 13-year-old Somalian who immigrated to Burlington after spending years fleeing civil war, hunger, and refugee camps. The eldest of six children, Mohammad has, since joining Chill, developed into a charismatic and determined leader with faultless English – something he claims to have struggled with upon his arrival in Vermont.

Abigail, from South Central Los Angeles was, at 10, the youngest Chill participant. After taking a couple runs with her and seeing her level of confidence, I would have never imagined that Abigail, along with her family from El Salvador, had, before joining the program, never seen snow, let alone ridden on it.

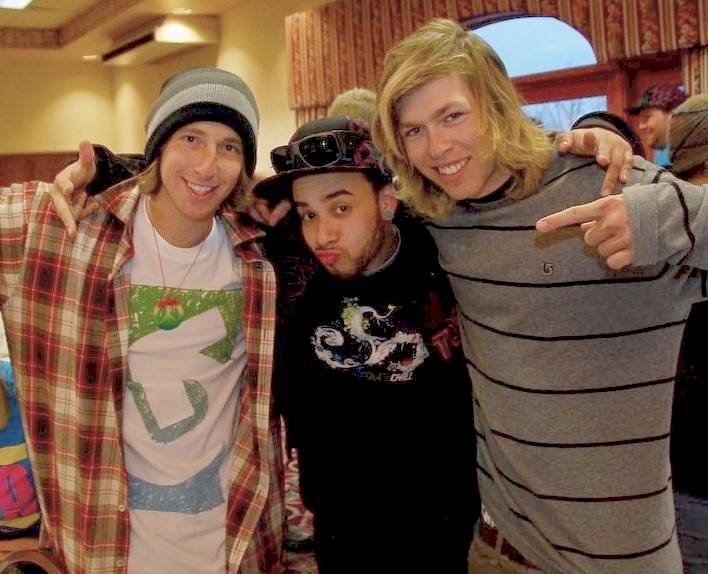

Chill participant Gio poses with Jack Mitrani and X Games champ Kevin Pearce. |

Gio, a 19-year-old from the housing projects of Brooklyn, has leveraged his Chill snowboarding experience to develop an artistic identity in graphic design and is looking forward to flexing his leadership skills as a snowboard instructor. Like many Chill “graduates,” he plans to return next season as a peer leader to help new participants adjust to the program.

As Chill looks forward to its 15th year in existence, Director Katherine McConnell is working diligently on the organization’s plan to introduce surfing and skateboarding to its list of offerings. “Our snowboard program has, over the years, been fine-tuned into an extraordinarily smooth-running operation – one that includes transportation, snowboard instruction, social services, and onsite medical services – so transferring that to a beach or skateboard park environment presents some obvious logistical challenges. We’re leveraging best practices from management, marketing, fundraising, and other partnerships to ensure that our warm-weather programming will be as successful as what we offer during the winter.”

With more than 50% of its funding coming from Burton Snowboards, Chill is actively reaching out to private donors and corporate sponsors that share its principles to provide support for these ambitious new objectives.

So there you have it, a unique, highly effective paradigm that combines snowboarding, social services, community activism (and a few other -isms I can’t yet articulate) to build the skills needed for success in these promising kids’ academic, professional, and personal lives. Ironically, one of the most economically inequitable sports in existence is giving disadvantaged young people the chance to level the playing field against more privileged peers and become their own agents of change. Think of it as a snowy variant of the “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime” proverb.

As I packed up to head back to the city, I put on my skier’s hat and asked Gio from Brooklyn a question that had been sticking in my craw all weekend, “Do they teach you guys not to sit down in the middle of a trail?”

He laughed: “Yeah, I’ve heard that earns you an automatic timeout.”