Mavrovo, Macedonia – "How

much is the bus to Mavrovo?" I asked the lady behind the counter.

She looked at me confused, and answered dismissively, "The

bus will come."

"OK. I want to buy a ticket."

"The bus will come," she repeated, then slid closed

the window for talking and looked away. She would not look back.

n

Macedonian was our language of communication, although I am

a native English speaker and she spoke native Albanian. I wasn’t sure who

was to be blamed for the communication breakdown; probably me.

I settled in the lobby with my book. Paul Theroux was struggling

with rickety China, and I figured that Macedonia was very modern and efficient

by that standard. An Albanian mother and her daughter were sitting next to

me. “Mirdita" I greeted them as they stared silently back. For

several minutes the daughter peered over my shoulder–an Albanian habit that

used to disconcert me but now just makes me laugh.

When the girl got bored with me, she turned back to her mother,

tugging at her shirt and giggling.

<SLAP!> The mighty hand of the mother hit the

child, then <SLAP!> backslapped the other way. I flinched.

The child reared back, then giggled and slapped her mother in

return. They both laughed and hugged.

Whatever, I thought, and returned to my book.

That was the first time. It happened again, several times,

this ritual of mother-child mutual abuse. Remembering that staring is an

acceptable Albanian pastime, I turned to watch them for awhile, the child

giggling and tugging at her mother, getting slapped, being quiet for a moment,

then giving her a big hug.

This was the beginning of a Macedonian ski trip.

|

The village of Mavrovo. |

I had made a mistake on my way to Mavrovo. Since the direct

bus from Skopje left in the afternoon and wouldn’t get into the ski center

until after dark, I decided I would take an early bus to Gostivar, a city

at the base of the mountains, then connect to Mavrovo. I thought I was being

clever, and how was I to know people from Gostivar don’t like to ski?

There was no bus to Mavrovo, but the bus to Debar left me at

a turnoff where a snow-covered one-lane road headed south. There was a sign,

"Mavrovo 5 km". One hour’s walk, I figured, and set off on foot

with my pack.

It was surprising how little traffic there was on the road.

After I had walked one kilometer a car passed. I signaled for a ride, but

the driver indicated he wasn’t going far and pulled over a hundred meters

ahead.

After 2 kilometers the second car on the road heeded my signal

and gave me a ride to the ski center. I asked the driver where I could find

a cheap place to stay, and he recommended a guy named Goran who operated a

mini-motel called Campari, the cheapest place in town.

I pitcured Goran as a kind middle-aged ski bum in a pullover

fleece, sort of a Macedonian John Denver. I imagined us spending the evening

by a fire, sipping hot cocoa, talking about the skier’s life. But when I

got to the hotel Goran wasn’t there. Instead there was Jordan, an unappealing

old man who acted annoyed by my presence and my accent.

"Who are you?" he snapped. "NATO? OSCE?"

These are the detested friends of the Albanian guerrillas in Macedonia. I

found him presumptuous to think that a 21-year old kid with a big backpack

was a NATO operative.

|

No one is likely to confuse the Campari with the Hotel

Atop Mavrovo’s summit. |

"No, no," I insisted. "I work for a humanitarian

organization in Skopje."

"A foundation?" he asked. I didn’t know what he meant

but since he was accusatory I decided he must mean one of those ‘obnoxious’

peace organizations goading the Macedonians to stick to the cease-fire. I

didn’t need this, and had the Campari not been the cheapest place in town

I would have marched right out. Instead, since money is more important than

pride sometimes, I bore out his insults and for $15 a night I settled into

an ample room, about thirty meters from the lifts.

I could have ordered a dinner from Jordan for $1.50, but I was

feeling too antagonistic for that. In my room I brought out my backpacker’s

stove and cooked a pot of pasta. This involved no small amount of fire hazard

and I certainly wouldn’t have done it if my idealized Goran was in charge,

but with Jordan managing–Captain Anti-America–I could not have cared less.

The next morning I decided to do an interview with a resort

official, trying my hand at professionalism.

"Now we have four machines to prepare the runs," the

manager of Mavrovo’s accommodations department told me. ‘Prepared’ meant

groomed, I quickly gathered. He leaned forward as he said this and exuded

pride.

"How many of the runs are prepared?"

"All of them!"

"Even the advanced runs?!"

"Every one!"

To the official, this was progress. Looking up the mountain

I saw beautiful steep pitches, the kind where great mogul fields are born,

and I imagined the pristine bumps being wiped away.

"There isn’t one mogul run?" I asked, trying not to

look sad.

"No. Not one." He was beaming. Those pesky moguls

had finally been put down.

They had lots of new equipment at Mavrovo, he said, due to privatization.

A company had bought the resort from the government, doubled the prices, and

were trying to turn a profit.

"Everybody was shocked when they doubled the prices,"

he said, "but now that they see our new equipment, they understand that

it’s worth it."

The new owners have bought snowmakers too, although they haven’t

been able to use them.

He explained, "Last year was too warm. This year we have

enough snow."

"Do you think they were unnecessary?"

"Absolutely not! They will be very useful, maybe next

year."

They also had updated their old chairlifts with new machines

and new cables. "Those old ones were about to fall apart. They were

totally unsafe," he told me, expecting me to be relieved that a horrible

accident was avoided, and now they’re fixed.

"Tell me about Mavrovo ski culture." I asked, trying

to get a more human feel of the area. He was confused by the question. What

is ski culture?

"Well, are there any Macedonian ski bums?"

"Ah. No. I don’t know anybody like that."

"What about après-ski?"

"Look, Mavrovo’s a quiet place. There’s two bars but one

of them is closed this year because of the fighting. We just built a covered

basketball court. Hopefully that will bring more activity."

"So, do you think Mavrovo can become an international resort?"

He shot me a cock-eyed look, which I deserved for asking such

a dumb question.

"No. We had no snow last year, and now with the fighting

and the economic collapse…we just want to get back to where we were when

Macedonia was still part of Yugoslavia. Then we had 3,000 skiers a day."

"And now?"

He frowned and turned silent. I told him it was time for me

to go skiing.

|

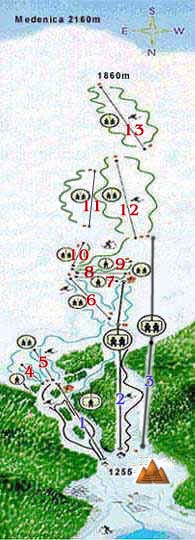

Beginner: Blue |

On the mountain I tried to estimate how many skiers were there

now. At first I thought there were twenty, but then decided I was underestimating

and that there might be as many as fifty or a hundred. Whatever the number,

it was a far cry from the 3,000 of halcyon Yugoslav days.

This emptiness gave Mavrovo a desolate feel, heightened by treeless

snowfields at the top meadow, comprehensive grooming, chairs without lift

attendants and a persistent fog.

But desolation can be a good thing. There were no lines, and

the skiers hardly made a dent in the powder gathered over the night.

Of the few skiers at Mavrovo, I was the only one interested

in the ungroomed parts of the mountain, and so I skied peacefully alone through

powder. The groomers had been everywhere they could, but some places were

too narrow or rocky or cliffy for them to flatten, and these had been preserved.

My anticipation of an empty day of sparse entertainment among

scattered jumps or quick forays into trees was not the case. On my first

run I discovered the unaltered purity of the slope under the one-person chairlift,

and then there was no turning back. The trees at Mavrovo have wide branches

that make tree skiing difficult, but not impossible, especially if one can

ski while ducking. It was an intense day for me, dividing my time between

the trees and the narrow runs. My muscles burned, and as the day ended I

was covered in sweat and snow.

Perhaps you, reader, are not a fan of the extremes as I am.

If this is the case, then I can pass on a hardy recommendation. Mavrovo’s

intermediate and beginner skiing was ample, with perfect snow quality. For

my fellow indulgers, Mavrovo is not intended for us and its charms are not

infinite, but for a small area tucked away in Macedonia it is not bad. It

doesn’t warrant a special trip, but if you’re in the area it is worth a visit.

For me, the $30 for hotel, rentals and lift tickets was cheap

by Western standards, but too great a chip out of my $75 monthly humanitarian

stipend, and I made plans to leave.

Retrieving my bag from the hotel I met Goran, the Campari’s

proprietor, who in fact was a very nice guy who spoke English well and wore

a cardigan rather than a fleece. But he made me tarry too long. I missed

the bus to Skopje and had to hitchhike home.